| Stimela (The Coal Train) (original) | Stimela (The Coal Train) (traducción) |

|---|---|

| There is a train that comes from Namibia and Malawi | Hay un tren que viene de Namibia y Malawi |

| there is a train that comes from Zambia and Zimbabwe, | hay un tren que viene de Zambia y Zimbabue, |

| There is a train that comes from Angola and Mozambique, | Hay un tren que viene de Angola y Mozambique, |

| From Lesotho, from Botswana, from Zwaziland, | De Lesotho, de Botswana, de Zwazilandia, |

| From all the hinterland of Southern and Central Africa. | De todo el interior de África Meridional y Central. |

| This train carries young and old, African men | Este tren lleva hombres africanos jóvenes y viejos |

| Who are conscripted to come and work on contract | Quienes son reclutados para venir y trabajar por contrato |

| In the golden mineral mines of Johannesburg | En las minas de minerales dorados de Johannesburgo |

| And its surrounding metropolis, sixteen hours or more a | Y su metrópolis circundante, dieciséis horas o más por |

| day | día |

| For almost no pay. | Por casi ningún pago. |

| Deep, deep, deep down in the belly of the earth | Profundo, profundo, profundo en el vientre de la tierra |

| When they are digging and drilling that shiny mighty | Cuando están cavando y perforando ese brillante y poderoso |

| evasive stone, | piedra evasiva, |

| Or when they dish that mish mesh mush food | O cuando sirven esa comida de papilla de malla de mish |

| into their iron plates with the iron shank. | en sus planchas de hierro con la caña de hierro. |

| Or when they sit in their stinking, funky, filthy, | O cuando se sientan en su apestoso, funky, sucio, |

| Flea-ridden barracks and hostels. | Cuarteles y albergues plagados de pulgas. |

| They think about the loved ones they may never see again | Piensan en los seres queridos que tal vez nunca vuelvan a ver. |

| Because they might have already been forcibly removed | Porque es posible que ya hayan sido removidos a la fuerza. |

| From where they last left them | De donde los dejaron por última vez |

| Or wantonly murdered in the dead of night | O sin sentido asesinado en la oscuridad de la noche |

| By roving, marauding gangs of no particular origin, | Por bandas errantes y merodeadoras sin origen particular, |

| We are told. | Nos dijeron. |

| they think about their lands, their herds | piensan en sus tierras, sus rebaños |

| That were taken away from them | Que les fueron quitados |

| With a gun, bomb, teargas and the cannon. | Con pistola, bomba, gas lacrimógeno y el cañón. |

| And when they hear that Choo-Choo train | Y cuando escuchan ese tren Choo-Choo |

| They always curse, curse the coal train, | Siempre maldicen, maldicen el tren del carbón, |

| The coal train that brought them to Johannesburg. | El tren de carbón que los trajo a Johannesburgo. |

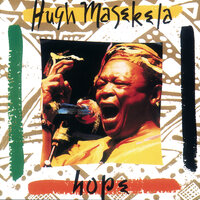

Traducción de la letra de la canción Stimela (The Coal Train) - Hugh Masekela

Información de la canción En esta página puedes leer la letra de la canción Stimela (The Coal Train) de -Hugh Masekela

Canción del álbum: Hope

En el género:Джаз

Fecha de lanzamiento:01.11.2009

Idioma de la canción:Inglés

Sello discográfico:Sheridan Square Entertainment

Seleccione el idioma al que desea traducir:

¡Escribe lo que piensas sobre la letra!

Otras canciones del artista:

| Nombre | Año |

|---|---|

| 2006 | |

| 2018 | |

| 2018 | |

Besame Mucho ft. Hugh Masekela, Hugh Masakela | 1977 |

| 2018 | |

| 2003 | |

| 2003 | |

| 2003 | |

| 2018 | |

| 2006 | |

| 1967 | |

| 2018 | |

| 2009 | |

| 2009 | |

Heaven In You ft. J'something | 2016 |

| 2016 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2018 |